Interview with history: YASIR ARAFAT

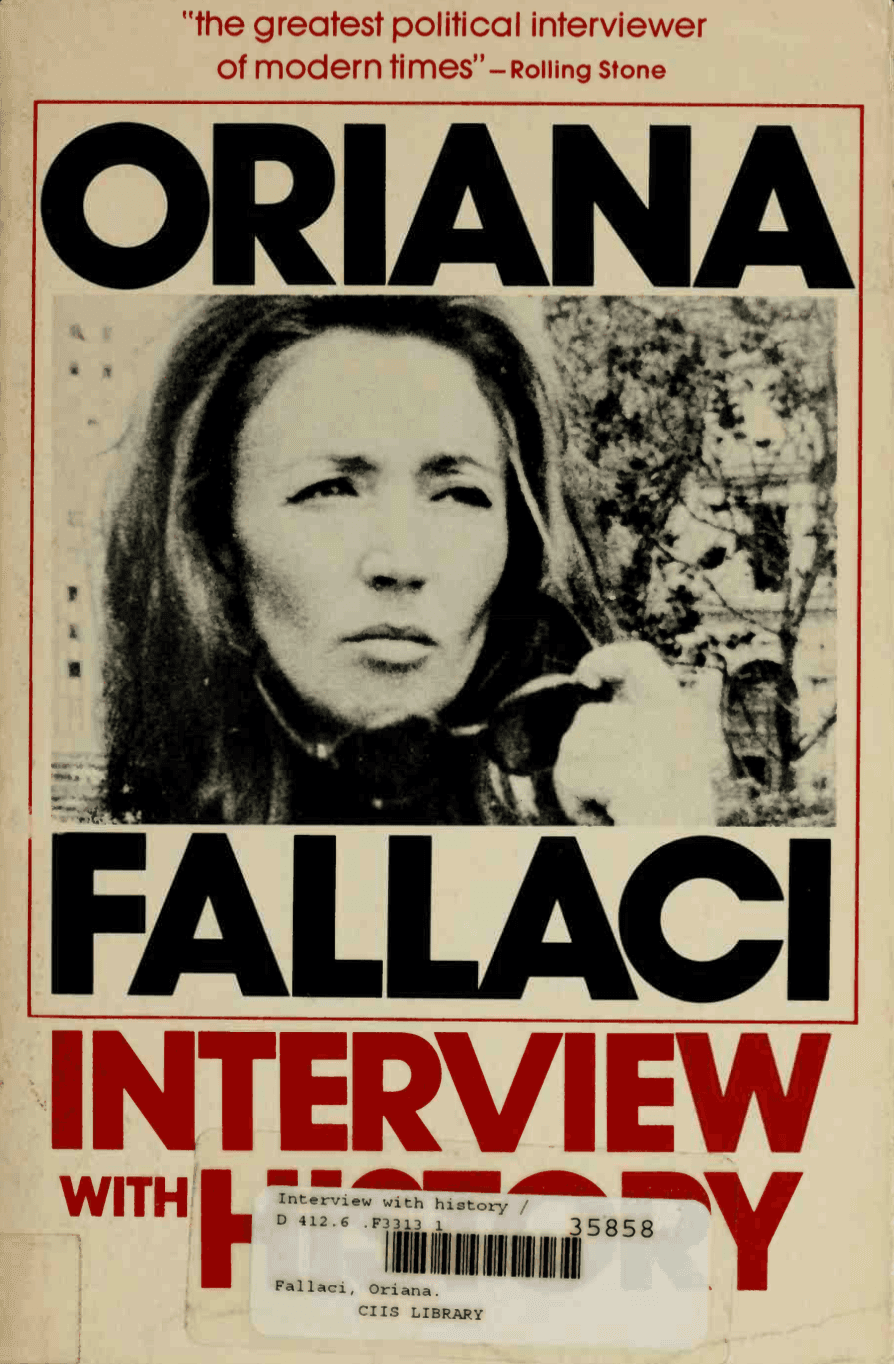

This interview was conducted by Oriana Fallaci in Jerusalem in November 1972, at a time when Yasser Arafat was known primarily as the leader of an armed revolutionary movement rather than an international statesman. Published later in Interview with History, the conversation captures Arafat before diplomatic normalization, before Oslo, and before the deliberate softening of his public image in Western media.

Nov 1, 1972

When he arrived, on the dot for the appointment, I remained for a moment uncertain, telling myself no, it couldn't be he. He seemed too young, too innocuous. At least at first glance, I noticed nothing in him that showed authority, or that mysterious fluid that always emanates from a leader to assail you like a perfume or a slap in the face. The only striking thing about him was his mustache, thick and identical with the mustaches worn by almost all Arabs, and the automatic rifle that he wore on his shoulder with the free-and-easy air of one who is never separated from it. Certainly he loved it very much, that rifle, to have wrapped the grip with adhesive tape the color of a green lizard: somehow amusing. He was short in height, five feet three, I'd say. And even his hands were small, even his feet. Too small, you thought, to sustain his fat legs and his massive trunk, with its huge hips and swollen, obese stomach.

All this was topped by a small head, the face framed by a kassiah, and only by observing this face were you convinced that yes, it was he, Yasir Arafat, the most famous guerrilla in the Middle East, the man about whom people talked so much, to the point of tedium. A very strange, unmistakable face that you would have recognized among a thousand in the dark. The face of an actor. Not only for the dark glasses that by now distinguished him like the eyepatch of his implacable enemy Moshe Dayan, but for his mask, which resembles no one and recalls the profile of a bird of prey or an angry ram. In fact, he has almost no cheeks or forehead. Everything is summed up in a large mouth with red and fleshy lips, then in an aggressive nose, and two eyes that though screened by glass lenses hypnotize you: large, shining, and bulging. Two ink spots. With those eyes he was now looking at me, courteously and absentmindedly. Then in a soft, almost affectionate voice, he murmured in English, "Good evening, I'll be with you in two minutes." His voice had a kind of funny whistle in it. And something feminine.

Those who had met him by day, when the Jordanian headquarters of Al Fatah was thronged with guerrillas and other people, swore they had seen around him a stirring excitement, the same as he aroused every time he appeared in public. But my appointment was at night, and at that hour, ten o'clock, there was almost no one. This helped to deprive his arrival of any dramatic atmosphere. Not knowing his identity, you would have concluded that the man was important only because he was accompanied by a bodyguard. But what a bodyguard! The most gorgeous piece of male flesh I had ever seen. Tall, slender, elegant: the type who wears camouflage coveralls as though they were black tie and tails, with the chiseled features of a Western lady-killer. Perhaps because he was blond and with blue eyes, I had the spontaneous thought that the handsome bodyguard was a Westerner, even a German. And perhaps because Arafat brought him along with such tender pride, I had the still more spontaneous thought that he was something more than a bodyguard. A very loving friend, let's say. In addition to him, who soon turned on his heel and disappeared, there was an ugly individual in civilian clothes who gave you dirty looks as though to say: "Touch my chief and I'll drill you full of holes." Finally there was the escort who was to act as interpreter, and Abu George, who was to write down questions and answers so that they could later be checked with my text.

These last two followed us into the room chosen for the interview. In the room there were a few chairs and a desk. With a provocative, exhibitionist gesture, Arafat put his automatic rifle on the desk and sat down with a smile of white teeth, pointed as the teeth of a wolf On his windbreaker, of gray-green cloth, a badge stood out with two Vietnam Marines and the inscription "Black Panthers against American Fascism." It had been given to him by two kids from California who called themselves American Marxists and had come with the pretext of offering him the alliance of Rap Brown, but in reality to do a film and make money. I told him so. He was struck by my judgment but not offended. The atmosphere was relaxed, cordial, but unpromising.I knew that an interview with Arafat is never good for obtaining memorable responses. And even less for getting any information out of him.

The most famous man in the Palestinian resistance is also the most mysterious; the curtain of silence surrounding his private life is so thick as to make you wonder if it doesn't constitute a trick to increase his publicity, a piece of coquetry to make him more precious. Even to obtain an interview with him is very difficult. With the excuse that he is always traveling, now to Cairo and now to Rabat, now to Lebanon and now to Saudi Arabia, now to Moscow and now to Damascus, they keep you waiting for days, for weeks, and if then they give it to you, it is with the air of presenting you with a special privilege or an exclusive right of which you're not worthy.

In the meantime, you try, of course, to gather information on his character, on his past. But wherever you turn, you find an embarrassed silence, only partly justified by the fact that Al Fatah maintains the greatest secrecy about its leaders and never supplies you with their biographies. Under-the-table confidences will whisper that he's not a communist, that he never would be even if Mao Tse-tung himself were personally to indoctrinate him; he is a soldier, they repeat, a patriot, and not an ideologue.

Indiscretions by now widespread will confirm that he was born in Jerusalem, sometime in the late twenties, that his family was noble and his youth spent in easy circumstances: his father owned an old fortune still largely unconfiscated. Such confiscation, which took place over the course of a century and a half, had been imposed by the Egyptians on certain land estates and on certain property in the center of Cairo. And then? Lx^t's sec… Then in 1947 Yasir had fought against the Jews who were giving birth to Israel and had enrolled in Cairo University to study engineering. In those years he had also founded the Palestinian Student Association, the same from which the nucleus of Al Fatah was to emerge. Having obtained his degree, he had gone to work in Kuwait; here he had founded a newspaper in support of the nationalist struggle, and he had joined a group called the Muslim Brothers. In 1955 he had gone back to Egypt to take an officers' training course and specialize in explosives; in 1963 he had helped especially in the birth of Al Fatah and assumed the name of Abu Ammar. That is, He Who Builds, Father Builder. In 1967 he had been elected president of the PLO, the Palestinian Liberation Organization, a movement that now includes the members of Al Fatah, of the Popular Front, of Al Saiqa, and so forth; only recently he had been chosen as the spokesman of Al Fatah, its messenger.

At this point, if you asked why, they spread their arms and answered, ''Well, someone has to do that too, one person or another, it doesn't make any difference." Of his daily life they told you nothing, except for the detail that he didn't even have a house. And it was true. When he wasn't staying with his brother in Amman, he slept on the bases or wherever he happened to be. It was also true that he was not married. There were no known women in his life, and despite the gossip of a platonic flirtation with a Jewish woman writer who had embraced the Arab cause, it really seemed that he could do without them: as I had suspected seeing him arrive with the handsome bodyguard.

You see, my suspicion is that, except for whatever details might serve to correct any inexactness, there is nothing more to say about Arafat. When a man has a tumultuous past, you feel it even when he conceals it, since his past is written on his face, in his eyes. But on Arafat's face you find only that strange mask placed there by Mother Nature, not by any experience for which he has paid. There is something unsatisfactory about him, something unrealized. Furthermore, if you stop to think about it, you realize that his fame burst out more through the press than through his exploits. Even worse, it was pulled out of the shadows by Western journalists and particularly by the Americans, who are always so skillful in inventing personalities or building them up. Just think of what they did with the bonzes in Vietnam, and with that nobody called the venerable Tri Quang. Of course, Arafat cannot be compared to Tri Quang. He is truly a creator of the Palestinian resistance, or one of its creators, and a strategist. Or one of its strategists. But this doesn't mean, all the less did it mean whenI met him, that he was the leader of the Palestinians in war. (The real brains of the movement, at the time, was Farolik EI Kaddoumi, called Abu Lotuf.) And, in any case, among all the Palestinians I met, Arafat remains the one who impressed me least of all.

Or should I say the one I liked least of all? One thing is certain: he is not a man born to be liked. He is a man born to irritate. It is difficult to feel sympathy for him. First of all for the silent refusal that he opposes to anyone attempting a human approach: his cordiality is superficial, his politeness (whenit exists) is formal, and a trifle is enough to make him hostile, cold, and arrogant. He warms up only when he gets angry. And then his soft voice becomes a loud one, his eyes become pools of hatred, and he looks as though he would like to tear you to pieces along with all his enemies.

Then, a lack of originality and charm characterizes all his replies. In my opinion, it is not the questions that count in an interview but the answers. If a person has talent, you can ask him or her the most banal thing in the world: he or she will always find the way to answer you brilliantly or profoundly. If a person is mediocre, you can put the most acute questions in the world to him or her: he or she always answer you as a mediocrity. If then you apply such a law to a man struggling between calculation and passions, watch out. After listening to him, you're likely to end up empty-handed. With Arafat I really found myself left empty-handed. He almost always reacted with indirect or evasive discourses, turns of phrase that contained nothing beyond his rhetorical intransigence, his constant fear of not persuading me.

He had no wish to consider, even as part of a dialectical game, the point of view of others. Nor is it enough to observe how the encounter between an Arab who believes in the war and a European who no longer believes in it is an immensely difficult encounter. Also because the latter remains imbued with her Christianity, with her hatred for hatred, and the other instead remains muffled inside his law of an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth, which is the epitome of any mistaken pride. But there comes a point at which such pride fails, and it is there where Yasir Arafat invokes the understanding of others or insists on dragging anyone who is disturbed by doubts behind his own barricade. To be interested in his cause, to admit its fundamental justice, to criticize its weak points, and therefore risk one's own physical and moral safety, are not enough for him. Even to this he reacts with the arrogance that I mentioned, the most unjustified haughtiness, and that absurd inclination to pick a quarrel. And aren't these the characteristics of mediocrity, of insufficient intelligence?

The interview lasted ninety minutes, a great part of which was wasted in translating the answers that he gave me in Arabic. He insisted on this himself—so as to ponder each word, I suppose. And each of those ninety minutes left me dissatisfied on the human level as well as on the intellectual or political. But I was amused to discover that he doesn't wear dark glasses in the evening because he needs them to see. He wears them to be noticed. In fact, whether by day or night, he sees very well. With blinkers, but very well. Hasn't he even made a career in recent years? Hasn't he got himself elected head of the whole Palestinian resistance and doesn't he travel around like a chief of state? As such, doesn't he go to the UN where he shouts, "An olive branch in one hand and a gun in the other hand," thus disturbing the best friends of the Palestinian cause? Nobody could ever accuse me of denying the rights of the Palestinians. I'm convinced that they will win because they must win. Yet it is bitter to see their rights advanced by inadequate people. And here is my personal judgment on Arafat: someone that history will inevitably reassess, like Kissinger, and restore to his real proportions.

Conducted November 1972 (Jerusalem)

ORIANA FALLACI: Abu Ammar, people talk of you so much but almost nothing is known about you and...

YASIR ARAFAT: The only thing to say about me is that I'm a humble Palestinian fighter. I became one in 1947, along with the rest of my family. Yes, that was the year when my conscience was awakened and I understood what a barbarous invasion had taken place in my country. There had never been one like it in the history of the world.

O.F.: How old were you, Abu Ammar? I ask because there's some controversy about your age.

Y.A.: No personal questions.

O.F.: Abu Ammar, I'm only asking how old you are. You're not a woman. You can tell me.

Y.A.: I said, no personal questions.

O.F.: Abu Ammar, if you don't even want to tell your age, why do you always expose yourself to the attention of the world and let the world look on you as the head of the Palestinian resistance?

Y.A.: But I'm not the head of it! I don't want to be! Really, I swear it. I'm just a member of the Central Committee, one of many, and to be precise the one who has been ordered to be the spokesman. That is to report what others decide. It's a great misunderstanding to consider me the head—the Palestinian resistance doesn't have a head. We try in fact to apply the concept of collective leadership and obviously the matter presents difficulties, but we insist on it since we believe it's indispensable not to entrust the responsibility and prestige to one man alone. It's a modern concept and helps not to do wrong to the masses who are fighting, to our brothers who are dying. If I should die, your curiosity will be exhausted—you'll know everything about me. Until that moment, no.

O.F.: I wouldn't say your comrades could afford to let you die, Abu Ammar. And, to judge by your bodyguard, I'd say they think you're much more useful if you stay alive.

Y.A.: No. Probably instead I'd be much more useful dead than alive. Ah, yes, my death would do much to help the cause, as an incentive. Let me even add that I have many probabilities of dying—it could happen tonight, tomorrow. If I die, it's not a tragedy—someone else will go around in the world to represent Al Fatah, someone else will direct the battles... I'm more than ready to die. I don't care about my safety as much as you think.

O.F.: I understand. On the other hand, you cross the lines into Israel once in a while yourself, don't you, Abu Ammar? The Israelis are convinced that you've entered Israel twice, and just escaped being ambushed. And they add that anyone who succeeds in doing this must be very clever.

Y.A.: What you call Israel is my home. So I was not in Israel but in my home—with every right to go to my home. Yes, I've been there, but much more often than only twice. I go there continually, I go when I like. Of course, to exercise this right is fairly difficult—their machine guns arc always ready. But it's less difficult than they think; it depends on circumstances, on the points chosen. You have to be shrewd about it, they're right about that. It's no accident that we call these trips "trips of the fox." But you can go ahead and inform them that our boys, the fedayeen, make these trips daily. And not always to attack the enemy. We accustom them to crossing the lines so they'll know their own land, and learn to move about there with ease. Often we get as far, because I've done it, as the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Desert. We even carry weapons there. The Gaza fighters don't receive their arms by sea—they receive them from us, from here.

O.F.: Abu Ammar, how long will all this go on? How long will you be able to resist?

Y.A.: We don't even go in for such calculations. We're only at the beginning of this war. We're only now beginning to prepare ourselves for what will be a long, a very long, war. Certainly a war destined to be prolonged for generations. Nor are we the first generation to fight. The world doesn't know or forgets that in the 1920s our fathers were already fighting the Zionist invader. They were weak then, because too much alone against adversaries who were too strong and were supported by the English, by the Americans, by the imperialists of the earth. But we are strong—since January 1965, that is since the day that Al Fatah was born, we're a very dangerous adversary for Israel. The fedayeen are acquiring experience, they're stepping up their attacks and improving their guerrilla tactics; their numbers are increasing at a tremendous rate. You ask how long we'll be able to resist—that's the wrong question. You should ask how long the Israelis will be able to resist. For we'll never stop until we've returned to our home and destroyed Israel. The unity of the Arab world will make this possible.

O.F.: Abu Ammar, you always invoke the unity of the Arab world. But you know very well that not all the Arab states are ready to go to war for Palestine and that, for those already at war, a peaceful agreement is possible, and can even be expected. Even Nasser said so. If such an agreement should take place, as Russia too expects, what will you do?

Y.A.: We won't accept it. Never! We will continue to make war on Israel by ourselves until we get Palestine back. The end of Israel is the goal of our struggle, and it allows for neither compromise nor mediation. The issues of this struggle, whether our friends like it or not, will always remain fixed by the principles that we enumerated in 1965 with the creation of Al Fatah. First: revolutionary violence is the only system for liberating the land of our fathers; second: the purpose of this violence is to liquidate Zionism in all its political, economic, and military forms, and to drive it out of Palestine forever; third: our revolutionary action must be independent of any control by party or state; fourth: this action will be of long duration. We know the intentions of certain Arab leaders: to resolve the conflict with a peaceful agreement. When this happens, we will oppose it.

O.F.: Conclusion: you don't at all want the peace that everyone is hoping for.

Y.A.: No! We don't want peace. We want war, victory. Peace for us means the destruction of Israel and nothing else. What you call peace is peace for Israel and the imperialists. For us it is injustice and shame. We will fight until victory. Decades if necessary, generations.

O.F.: Let's be practical, Abu Ammar. Almost all the fedayeen bases are in Jordan, others are in Lebanon. Lebanon has little wish to fight a war, and Jordan would very much like to get out of it. Let's suppose that these two countries, having decided on a peaceful agreement, decide to prevent your attacks on Israel. In other words, they prevent the guerrillas from being guerrillas. It's already happened and will happen again. In the face of this, what do you do? Do you also declare war on Jordan and Lebanon?

Y.A.: We can't fight on the basis of "ifs." It's the right of any Arab state to decide what it wants, including a peaceful agreement with Israel; it's our right to want to return home without compromise. Among the Arab states, some are unconditionally with us. Others not. But the risk of remaining alone in fighting Israel is a risk that we've foreseen. It's enough to think of the insults they hurled at us in the beginning; we have been so maltreated that by now we don't pay any attention to maltreatment. Our verv formation,I mean, is a miracle. 1 he candle that was lighted in 1965 burned in the blackest darkness. But now we are many candles, and we illuminate the whole Arab nation. And beyond the Arab nation.

O.F.: That's a very poetic and very diplomatic answer, but it's not the answer to what I asked you, Abu Ammar. I asked you: If Jordan really doesn't want you any more, do you declare war on Jordan?

Y.A.: I'm a soldier and a military leader. As such I must keep my secrets—I won't be the one to reveal our future battlefields to you. If I did, Al Fatah would court-martial me. So draw your own conclusions from whatI said before. I told you we'll continue our march for the liberation of Palestine to the end, whether the countries in which we find ourselves like it or not. Even now we are in Palestine.

O.F.: We're in Jordan, Abu Ammar. And I ask you: But what does Palestine mean? Even Palestine's national identity has been lost with time, and its geographical borders have also been lost. The Turks were here, before the British Mandate and Israel. So what are the geographical borders of Palestine?

Y.A.: We don't bring up the question of borders. We don't speak of borders in our constitution because those who set up borders were the Western colonialists who invaded us after the Turks. From an Arab point of view, one doesn't speak of borders; Palestine is a small dot in the great Arabic ocean. And our nation is the Arab one, it is a nation extending from the Atlantic to the Red Sea and beyond. What we want, ever since the catastrophe exploded in 1947, is to free our land and reconstruct the democratic Palestinian state.

O.F.: But when you talk of a state, you have to say too within what geographical limits this state is formed or will be formed! Abu Ammar,I ask you again: what are the geographical borders of Palestine?

Y.A. : As an indication, we may decide that the borders of Palestine are the ones established at the time of the British Mandate. If we take the Anglo-French agreement of 1918, Palestine means the territory that runs from Naqurah in the north to Aqaba in the south, and then from the Mediterranean coast that includes the Gaza Strip to the Jordan River and the Negev Desert.

O.F.: I see. But this also includes a good piece of land that today is part of Jordan, I mean the whole region west of the Jordan. Cisjordania.

Y.A.: Yes. But I repeat that borders have no importance. Arab unity is important, that's all.

O.F.: Borders have importance if they touch or overlap the territory of a country that already exists, like Jordan.

Y.A.: What you call Cisjordania is Palestine.

O.F.: Abu Ammar, how is it possible to talk of Arab unity if from now on such problems come up with certain Arab countries? Not only that, but even you Palestinians are not in agreement. There is even a great division between you of Al Fatah and the other movements. For example, with the Popular Front.

Y.A.: Every revolution has its private problems. In the Algerian revolution there was also more than one movement, and for all I know, even in Europe during the resistance to the Nazis. In Vietnam itself there exist several movements; the Vietcong are simply the overwhelming majority, like we of Al Fatah. But we of Al Fatah include ninety-seven percent of the fighters and are the ones who conduct the struggle inside the occupied territory. It was no accident that Moshe Dayan, when he decided to destroy the village of El Heul and mined 218 houses as a punitive measure, said, "We must make it clear who controls this village, we or Al Fatah." He mentioned Al Fatah, not the Popular Front. The Popular Front... In February 1969 the Popular Front split into five parts, and four of them have already joined Al Fatah. Therefore we're slowly being united. And if George Habash, the leader of the Popular Front, is not with us today, he soon will be. We've already asked him to join us; there's basically no difference in objectives between us and the Popular Front.

O.F.: The Popular Front is communist. You say that you're not set up that way.

Y.A.: There are fighters among us representing all ideas; you must have met them. Therefore among us there is also room for the Popular Front. Only certain methods of struggle distinguish us from the Popular Front. In fact we of Al Fatah have never hijacked an airplane, and we have never planted bombs or caused shooting in other countries. We prefer to conduct a purely military struggle. That doesn't mean, however, that we too don't have recourse to sabotage—inside the Palestine that you call Israel. For instance, it's almost always we who set off bombs in Tel Aviv, in Jerusalem, in Eilat.

O.F.: That involves civilians, however. It's not a purely military struggle.

Y.A.: It is! Because, civilians or military, they're all equally guilty of wanting to destroy our people. Sixteen thousand Palestinians have been arrested for helping our commandos, eight thousand houses of Palestinians have been destroyed, without counting the tortures that our brothers undergo in their prisons, and napalm bombings of the unarmed population. We carry out certain operations, called sabotage, to show them that we're capable of keeping them in check by the same methods. This inevitably hits civilians, but civilians are the first accomplices of the gang that rules Israel. Because if the civilians don't approve of the methods of the gang in power, they have only to show it. We know very well that many don't approve. Those, for example, who lived in Palestine before the Jewish immigration, and even some of those who immigrated with the precise intention of robbing us of our land. Because they came here innocently, with the hope of forgetting their ancient sufferings. They had been promised Paradise, here on earth, and they came to take over Paradise. Too late they discovered that instead it was hell. Do you know how many of them now want to escape from Israel? You should see the emigration applications that pile up at the Canadian embassy in Tel Aviv, or the United States embassy. Thousands.

O.F.: Abu Ammar, you never answer me directly. But this time you must do so. What do you think of Moshe Dayan?

Y.A.: That's a very embarrassing question. How can I answer? Let's say this: I hope that one day he'll be tried as a war criminal, whether he's really a brilliant leader or whether the title of brilliant leader is something he's bestowed on himself.

O.F.: Abu Ammur, I seem to have read somewhere that the Israelis respect you more than you respect them. Question: Are you capable of respecting your enemies?

Y.A.: As fighters, and even as strategists... sometimes yes. One must admit that some of their war tactics are intelligent and can be respected. But as persons, no, because they always behave like barbarians; there's never a drop of humanity in them. People often talk of their victories; I have my own ideas about their victory of 1967 and the one in 1956. The one in 1956 shouldn't even be called a victory; that year they only queued up after the British and French aggressors. And they won with the help of the Americans. As for their 1967 victory, they owe it to the help of the Americans. Money comes in lavish and uncontrolled donations from the Americans to Israel. And besides money, they also get lavish shipments of the most powerful weapons, the most advanced technology. The best the Israelis possess comes from outside—this story of the wonders that they have achieved in our country ought to be re-examined with a greater sense of reality. We know very well what the wealth of Palestine is and is not: you don't get more than just so much out of our land; you don't create gardens out of the desert. Therefore the major part of what they possess comes from outside. And from the technology with which the imperialists supply them.

O.F. : Let's be honest, Abu Ammar. They've put and are putting technology to good use. And as soldiers, they come off well.

Y.A.: They have never won by their positive aspects; they've always won through the negative aspects of the Arabs.

O.F.: That too is part of the game of war, Abu Ammar. Besides, they've also won because they're brave soldiers.

Y.A.: No! No! No! No, they're not! In hand-to-hand combat, face to face, they're not even soldiers. They're too afraid of dying, they show no courage. That's what happened in the battle of Karameh and that's what happened the other day in the battle of El Safir. Crossing the lines, they came down on Wadi Fifa with forty tanks, on Wadi Abata with ten tanks, on Khirbet el-Disseh with ten tanks and twenty jeeps with 106-caliber machine guns. They preceded the advance with a heavy artillery bombardment and after ten hours sent in their planes, which bombed the whole area indiscriminately, and then helicopters to fire missiles against our positions. Their objective was to reach the valley of El Nmeiri. They never reached it; after a twenty-five-hour battle, we drove them back across the lines. Do you know why? Because we used more courage than they did. We surrounded them, we attacked them in the rear with our rifles, with our bazookas face to face, without fear of dying. It's always the same story with the Israelis. They're good at attacking with planes because they know we have no planes, with tanks because they know we have no tanks, but when they run into face-to-face resistance, they don't risk any more. They run away. And what good is a soldier who takes no risks, who runs away?

O.F.: Abu Ammar, what do you say of the operations carried out by their commandos? For example, when their commandos go to Egypt to dismantle a radar station and carry it away? You need a little courage for something like that.

Y.A.: No, you don't. Because they always look for very weak, very easy objectives. Those are their tactics, which,I repeat, are always intelligent but never courageous in that they consist in employing enormous forces in an undertaking of whose success they're a hundred percent sure. They never move unless they're certain that everything will go well, and if you take them by surprise, they never fully commit themselves. Every time they've attacked the fedayeen in strength, the Israelis have been defeated. Their commandos don't get by us.

O.F.: Maybe not by you, but they do get by the Egyptians.

Y.A.: What they're doing in Egypt is not a military action, it's a psychological war. Egypt is still their strongest enemy, and so they're trying to demoralize it and undermine it through a psychological war incited by the Zionist press with the help of the international press. Their game consists in propagandizing an action by exaggerating it. Everybody falls for it because they possess a powerful press agency. We have no press agency, nobody knows what our commandos are doing, our victories go unnoticed because we have no wire service to transmit the news to newspapers that anyway wouldn't publish it. So no one knows, for example, that on the same day that the Israelis were stealing the radar station from the Egyptians, we entered an Israeli base and carried off five large rockets.

O.F.: I wasn't talking about you, I was talking about the Egyptians.

Y.A.: There's no difference between Palestinians and Egyptians. Both are part of the Arab nation.

O.F.: That's a very generous remark on your part, Abu Ammar. Especially considering that your family was actually expropriated by the Egyptians.

Y.A.: My family was expropriated by Farouk, not by Nasser. I know the Egyptians well because I went to the university in Egypt, and I fought with the Egyptian army in 1951, 1952, and 1956. They're brave soldiers and my brothers.

O.F.: Let's get back to the Israelis, Abu Ammar. You say that with you they always suffer huge losses. How many Israelis do you think you've killed up to this date?

Y.A.: I can't give you an exact figure, but the Israelis have confessed to having lost, in the war against the fedayeen, a percentage of men that is higher than that of the Americans in Vietnam—in proportion, of course, to the population of the two countries. And it's indicative that, after the 1967 war, their traffic deaths increased ten times. In short, after a battle or a skirmish with us, it comes out that a lot of Israelis have died in automobile accidents. This observation has been made by the Israeli newspapers themselves, because we know that the Israeli generals never admit to losing men at the front. But I can tell you that, going by the American statistics, in the battle of Karameh they lost 1247 men between dead and wounded.

O.F.: And do you pay an equally heavy price?

Y.A.: Losses to us don't count, we don't care if we die. Anyway, from 1965 to today, we have had slightly over nine hundred dead. But you must also consider the six thousand civilians dead in air raids and our brothers who die in prison under torture.

O.F.: Nine hundred dead can be many or few, depending on the number of combatants. How many fedayeen are there altogether?

Y.A.: To tell you that figure, I would have to ask permission from the Military Council, and I don't think they would give it to me. But I can tell you that at Karameh we were only 392 against 15,000 Israelis.

O.F.: Fifteen thousand? Abu Ammar, maybe you mean 1500.

Y.A.: No! No! No!I said 15,000, 15,000! Including, of course, the soldiers employed with the heavy artillery, the tanks, the planes, the helicopters, and the parachutists. As troops alone, they had four companies and two brigades. What we say is never believed by you Westerners, you listen to them and that's all, you believe them and that's all, you report what they say and that's all!

O.F.: Abu Ammar, you're an unfair man. I am here and I'm listening to you. And after this interview I'll report word for word what you've told me.

Y.A.: You Europeans are always for them. Maybe some of you are beginning to understand us—it's in the air, one can sense it. But essentially you're still for them.

O.F.: This is your war, Abu Ammar, not ours. And in this war of yours we are only spectators. But even as spectators you can't ask us to be against the Jews and you shouldn't be surprised if in Europe the Jews are often loved. We've seen them persecuted, we've persecuted them. We don't want it to happen again.

Y.A.: Sure, you have to pay your debts to them. And you want to pay them with our blood, with our land, rather than with your blood, your land. You go on ignoring the fact that we have nothing against the Jews, we have it against the Israelis. The Jews will be welcome in the democratic Palestinian state. We'll offer them the choice of staying in Palestine when the moment arrives.

O.F.: But, Abu Ammar, the Israelis are Jews. Not all Jews can identify themselves with Israel, but Israel can't help identifying itself with the Jews. And you can't ask the Jews of Israel to go wandering around the world once more and thereby end up in extermination camps. That's unreasonable.

Y.A.: So you want to send us wandering around the world.

O.F.: No. We don't want to send anybody. You least of all.

Y.A.: But wandering around is what we're doing now. And if you're so anxious to give a homeland to the Jews, give them yours you have a lot of land in Europe, in America. Don't presume to give them ours. We've lived on this land for centuries and centuries; we won't give it up to pay your debts. You're committing an error even from a human point of view. How is it possible that the Europeans don't recognize it even while being such civilized people, so advanced, and perhaps more advanced than on any other continent? And yet you too have fought wars of liberation, just think of your Risorgimento.

November, 1972 | © Oriana Fallaci

Archival material reproduced here for educational and research purposes under fair use. Original copyright belongs to the respective publisher.

About

Every headline has a history. We go back to the archives of the same media you read today — to show how their own words have changed. Facts don’t expire. Narratives do.

Featured Posts

Explore Topics